The disorienting music of Mt. Moon

April 29, 2022

As part of MUSI 26819: Video Game Music as Play and Discipline (Spring 2019) taught by Julianne Grasso at UChicago, I wrote this essay about the disorienting music of Mt. Moon.

I also transcribed and annotated the piece—I recommend following along with the sheet music as I describe it in the essay.

I hope you enjoy it!

Introduction

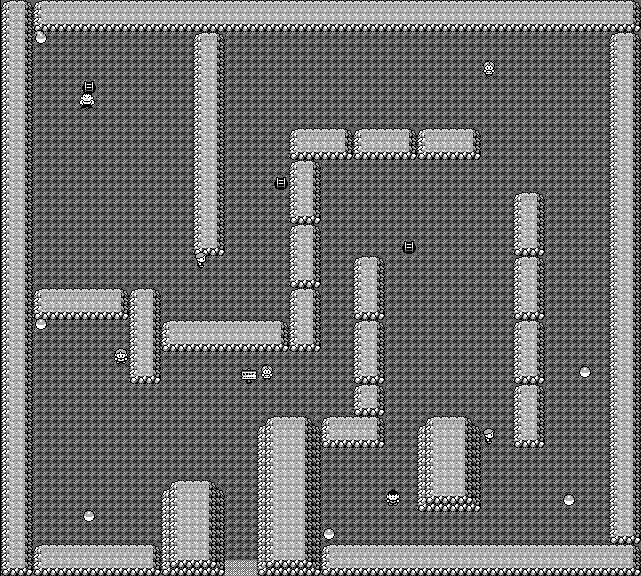

A challenge that players of the role-playing game Pokémon Red and Blue (1996) must face early in their adventures is to navigate through the large and foreboding Mt. Moon via a series of interconnected caves. The cave walls are indistinguishable from one another (Figure 1), which—compounded with the fact that players can only see a small portion of the cave at a time—makes navigating the caves of Mt. Moon a disorienting experience. However, it is not just the caves themselves that cause this confusing experience: their music serves to disorient as well. Pokémon composer Junichi Masuda creates a musical backdrop to the caves that both micro- and macroscopically reflects and enhances the disorienting nature of Mt. Moon by weaving together nonfunctional harmonies, complex rhythms, a whole-tone melody, and a deceptive musical form.

Figure 1. The entrance to Mt. Moon. Credit to user Clarky13 on Bulbapedia.

Harmony

The single discernible chord of Mt. Moon’s harmonies is the augmented triad. As it is completely symmetric, the augmented triad lacks a strong chordal root, leaving listeners with no tonic upon which to ground themselves. Moreover, each augmented triad lingers for four full measures, creating a state of harmonic limbo as listeners become accustomed to the sound but never experience a harmonic development or resolution.

When the harmony does change from one augmented triad to the next, the relationship between each chord appears nearly arbitrary: perfect fourths in some places, tritones in others, and semitones in yet others. This nonfunctional harmonic progression suggests a sense of unsettlement or confusion; without knowing the entire piece ahead of time, it is impossible to determine where the harmony will travel next.

As such, both the individual chords Masuda uses as well as the relationships between these chords act as disorienting forces to the player.

Rhythm

Although subtler than the harmony, the rhythm of Mt. Moon’s music is a disorienting force in its own right. Just as the piece’s harmony served to disorient on both a local (intra-chordal) and global (inter-chordal) scale, so too do its rhythms: within each rhythmic section, Masuda divides the rhythmic pulse unevenly and in complex ways, and, between each of these sections, Masuda modulates the rhythm of the piece unpredictably and often rapidly.

The first section of the piece begins in what could be heard as 4/4 or 8/8 time with a 3+3+2 rhythmic subdivision; although this rhythm is not particularly uncommon, it sets a precedent for the rest of the piece that the pulse will not fall on the beats typically implied to be accented in 4/4 time.1

Starting at m. 21, the piece introduces four rhythmically complex variations on the main melody, each beginning with a measure of 10/8 (subdivided as 2+3+3+2 rather than the more standard “clave” rhythm of 3+3+2+2) followed by either

- two measures of 8/8 (3+3+2) and one measure of 6/8 (3+3),

- one measure of 8/8 (3+3+2) and two measures of 6/8 (3+3), or

- three measures of 6/8 (3+3).

This level of rhythmic complexity is evident in other parts of the piece, too. For example, at m. 42, after the relative stability of five measures of 6/8, Masuda adds in a measure of 7/8 (3+3+1) that recurs nowhere else in the piece before looping back to the starting 8/8. Juxtaposed with the repetitive 6/8 measures prior to it, the extra beat of the 7/8 measure gives the impression of a misstep, causing the listener to lose their place in the piece—if they had not already lost it from the prior rhythmic modulations.

As a result of these varied modulations between intricate rhythms, listeners are hard-pressed to maintain a sense of where they are in the piece, reflecting and amplifying the very same sensation that is experienced when spelunking in the caves of Mt. Moon.

Melody

In tandem with the harmony and rhythm, the melody of the piece further contributes to player disorientation. Save for a single note, the entire melody lies within the whole-tone hexatonic scale of the augmented triad underlying it. Like the augmented triad, the whole-tone scale is perfectly symmetric, with no strong indicator of tonic. The only note of the melody not in this scale is a chromatic neighbor tone first appearing as the last note of m. 3. This neighbor tone is actually the leading tone of the corresponding major scale (B major for m. 3), and, as such, serves as the lone source of harmonic directionality in the melody.

However, any brief sense of harmonic relief the note instills in the listener is quickly dissipated because (1) the leading tone is not supported by a dominant chord, and (2) the “resolution” back to the tonic is displaced by further travel upward to the second degree of the scale (as in m. 4). After a complete introduction of the melody, the piece shifts harmonically to the $\text{IV}^\text{aug}$ chord and the melody repeats, transposed to the key of $\text{IV}$.

Harmonically, the shift from $\text{I}^\text{aug}$ to $\text{IV}^\text{aug}$ (and back again) makes little functional sense, but from a scalar point of view, the logic is clear: the $\text{IV}$ whole-tone scale is the dual to the I whole-tone scale—each uses precisely the six notes the other does not.

By keeping the melody largely within the hexatonic whole-tone scale, Masuda imbues the shifting harmonies with even more disorientation.

Form

On a larger scale, Masuda combines these harmonies, rhythms, and melodies into a piece whose musical form itself disorients. The piece is in ABA'C form, where the A' section takes the melody from the A section and develops it by exploring new tonal areas and rhythmic patterns.

Because of the high Pokémon **encounter rate in Mt. Moon, the background music often resets, meaning that B, A', and C sections are rarely (if ever) heard, leading to surprise and disorientation when they are heard. If the player eventually does hear the A' section, they are greeted with a few, subtle differences from the A section, which may be especially difficult to discern with the B section serving as a auditory separator between the sections:2 the melody surreptitiously changes from a $\hat{3}$–$\hat{2}$ introduction to $\hat{2}$–$\hat{1}$ (m. 1 vs. m. 21), the harmonies are slightly expanded upon (an added $\#\text{IV}^\text{aug}$ chord, mm. 25–32), the new 10/8 rhythm feels off-kilter with an extra quarter note inserted into the melodic introduction, and the additional new rhythms force the melody to be altered slightly in each melodic variation. These differences are subtle, but, just as a player lost in the featureless and confusingly similar caves of Mt. Moon may ask “Have I been here before?”, the musical form of the piece prompts listeners to do the same.

Conclusion

At both small and large scales, Junichi Masuda instills ambiguity and destabilization into the harmony, rhythm, melody, and form of the music of Mt. Moon. In doing so, Masuda creates a piece of music that embodies and amplifies the player’s experience of traversing the confusing caves of Mt. Moon: complete disorientation.

Acknowledgements

- Thanks to AudioOverload and Zophar’s Domain for making transcription easier!

- Thanks to user QWERTYkid911 on ninsheetmusic.org for posting a piano reduction of the track. After transcribing the piece by myself, I looked online to see how other people had transcribed it, and made the following changes to my transcription after seeing QWERTYkid911’s:

- m. 42 used to be 6/8 followed by a measure of 9/8, but it is now 7/8 followed by 8/8

- At first, I didn’t notice the three half-measure delay of the bassline in the B section, so I have now shifted the bassline accordingly

- I changed “ritardando” in the B section to “molto ritardando” because, well, it really slows down!

In my transcription, I notated this rhythm as being in 8/8 rather than 4/4 to be consistent with the remainder of the piece.

The B section serves as an excellent separator because it is disorienting in its own right: the tempo gradually slows, the melody falls ever downward, and the bassline descends chromatically and is offset from the overarching meter (there are three half-measures of A# in the bass followed by five half-measures of chromatic descent).